Phật Giáo Nhật Bản sự hoà hợp với đạo Shinto

bài viết của ky' giả Sten McCarty

Kotohira Shrine, where about four million

pilgrims a year go up the 785 stone steps

Người ta đã khám phá đưọc những cổ vật rải rác đó đây, cộng với những tầng lớp truyền thuyết từ nhiều tôn giáo, đã có liên hệ với The Elephant's Head Mountain Range (Zozuzankei) trên đảo Shikoku. Không ai có thể khéo léo đặt những miếng puzzle chung lại với nhau trong sự so sánh và nhắc đến một tôn giáo triết học của thời ky` Heian tại Nhật Bản. Theo sự khảo cứu thi` toàn vùng Zozuzankei như là một nơi thiêng liêng. Giống như vùng Phương Ðông khác, nó lên đến cực điểm trong sự cố gắng thống nhất các trường phái Mandala đại diện cho miền núi và văn hóa tôn giáo của Ấn Ðộ, Trung Hoa và Nhật Bản.

Ngày hôm nay tại chân núi Zozuzankei, trong quận nhỏ Kagawa có hai thị trấn nhỏ nhưng rất nổi tiếng là thị trấn của tôn giáo Monzen-machi. Kotohira Shrine, co`n gọi là Kompira-san, nơi đây có nhiều vị tu sĩ Shinto tu hành. Tu viện Zentsuji là một tu viện Shingon lớn nơi quê hương của Kukai (774-835), một vị cao tăng của Nhật Bản. Ngài học tại thủ đô của hoàng đế Chang-an. Kukai thật sự đã đưa thời ky` Heian vào thời ky` vàng son cho nước Nhật.

Gần đảo Seto, người ta kiếm thấy một tảng đá lớn tuổi 10,000 năm về truớc đó là tượng ngà voi. Cũng giống như ngọn núi đầu voi (Zozuzan, những người Phật tử gọi là núi Kompira) và gần nơi sinh quán của Kukai tại thị trấn Zentsuji, một tảng đá lớn tuổi khác được ti`m thấy tảng đá với tuổi mới của thời đại Jomon.

Một vài chuông đồng của thời đại Yayoi trước khi được chuyển sang đời thượng cổ Nhật Bản, đã được kiếm thấy tại Kyushu gần miền đất của Phương Ðông, có trên một chục cái được kiếm thấy gần Kotohira và Zentsuji. Những cái kiếm bằng đồng được kiếm thấy tại thị trấn Zentsuji thi` hầu hết được kiếm thấy tại Nhật Bản. Tại Kotohira Shrine người ta kiếm thấy một cái chuông tuổi chừng 2,000 năm. Những nhà khảo cổ đã khám phá ra một chuyện cực ky` ly' thú vào thời đại Yayoi đó là họ đã kiếm thấy một chuông đồng trên ngọn núi, nơi kukai khi co`n là đứa trẻ mà người ta tin tưởng rằng đã gặp Đức Phật.

Có những lúc đạo Phật và đạo Shinto, sự kết hợp của Kompira Daigongen trở thành đồng nhất với Shinto Kami của núi Kompira, O-Kuni-nushi-no-mikoto, một trong những vị trời chính của Nhật Bản, vị trời đó có liên hệ một cách mơ hồ với những con cá sấu ở trong White Hare của huyền thoại Inaba ở Kojiki. Về sau những Phật tử của Phật giáo và đạo Shinto có thể coi như có niềm tin giống nhau, và hoà hợp lại thành một tôn giáo.

Minh Hạnh dịch

Buddhist Syncretism in Japan

by Steve McCarty

Originally published in the Encyclopedia of Monasticism,

pp. 1223-1225. Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers (September 2000)

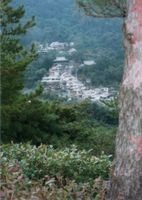

Bewildering archaeological discoveries, combined with layers of lore from many religions, have been associated with the Elephant's Head Mountain Range (Zozuzankei) on Shikoku Island, remore from familiar political and religious centers. No one has put all the puzzle pieces together in a comparative Asian perspective and with reference to religious syncretism of the Heian period in Japan. Reconstructing the 'lost chord' from oblivion leads to the conclusion that premodern Japanese viewed the whole Zozuzankei as a sacred area. Like certain other East Asian spaces, it culminates in a syncretic mandala of mountains representing and uniting the religious cultures of India, China and Japan. Japanese people have tended to live on the plains, perceiving the mountains and the sea beyond their purview the abode of the sacred. On these mountains emerged examples of religious syncretism, often in the guise of triads.

Today at the foot of the Zozuzankei in tiny Kagawa prefecture are two small but famous religious towns (monzen-machi) that grew from the gates of a major Shinto shrine and a major Buddhist temple. Kotohira Shrine, called Kompira-san after its mountain, houses many Shinto priests, whereas Zentsuji Temple is a large Shingon monastery commemorating the birthplace of Kukai (774-835), one of Japan's greatest religious figures. He studied in the T'ang dynasty capital of Ch'ang-an at a peak of Chinese civilization, just as it was drawing inspiration from the last flowering of Buddhism in India. Kukai thus helped turn the dawning Heian period into a golden age for Japan.

The depth as well as breadth of religious phenomena concentrated in the space of a few miles is revealed in some of the archaeological discoveries. Nearby in the Seto Inland Sea, which was formed when land dropped down about 10,000 years ago, an Old Stone Age mammoth ivory doll has been found. Similarly, on Mount Elephant's Head (Zozuzan, a Buddhist name for Mount Kompira) and near Kukai's birthplace in Zentsuji, traces of Old Stone Age culture have been discovered along with New Stone Age culture of the Jomon period. Although Mount Elephant's Head is now miles inland, seashells have been found near the summit, indicating that the Zozuzankei formed the coastline a few millennia ago.

Before any ritual bronze bells (dotaku) of the Yayoi period that transformed ancient Japan were found in Kyushu nearest the Asian mainland, over a dozen have been found around Kotohira and Zentsuji. Flat bronze swords (doken) found in Zentsuji constitute the most ever found in Japan. Around the Kotohira Shrine was found a 2,000-year-old bronze bell, now a designated national treasure in the Tokyo National Museum, depicting a building similar in proportions to those of the Grand Shrine of Izumo on the Sea of Japan. Then archaeologists were stunned by the finding of a Yayoi period ritual bell on the mountain where Kukai as a child was believed to have met the Buddha.

Tumuli of the following Kofun period number over 400 in Zentsuji, decorated with boats to carry the departed to the afterworld of the sea. Kompira-san is thought to have been a seafaring capital of ancient Japan, worshiping a sea god (kami). Such sites could be termed proto-Shinto, reflecting the fact that Shintoism was late to institutionalize in response to Buddhism. In Zentsuji some Kofun period tumuli have been turned into Shinto shrines as conduits to the kami (shintai), uniting ancestors with gods over millennia. Moreover, evidently an indigenous animism viewed a mountain such as Mount Kompira (or Zozuzan, Elephant's Head Mountain) as itself the body of a god (shintaizan; cf. shintai, the conduit to a god).

Into this congeries entered Heian period esoteric Buddhism, reinforcing the deeper stratum of mountain worship by associating each temple with a mountain. A religious pluralism based on assimilation reconciled the many Asian religious influences then current with the ex post facto theory that all their representative divinities emanated from original Buddhas (honji suijaku setsu). Bureaucratic restrictions on the number of monks that could be ordained had led to spontaneous forms of Japanese Buddhism that favored mountain asceticism (especially Shugendo). It has been shown in connection with Mount Kumano and Mount Hiei that the sacred space outdoors was organized into a mandala of Buddhist-Shinto syncretism that the ritual practitioner could traverse.

Similarly at Mount Kompira, by affinity of name with its sea god, the Buddhist guardian Kumbhira, originally a Hindu crocodile god of the Ganges River, was said to have flown to Japan and became Kompira. He was accompanied by Elephant's Head Mountain near Bodh Gaya, which figures in the hagiography of the Buddha. Mount Kompira does resemble an elephant's head, although not as much as conventionalized views by Hiroshige and other artists. Given the animism of mountain worship, various divinities could be perceived in Hindu fashion as riders on their mounts. Beyond being a crocodile god, suitable to protect seafarers, Kompira was elevated to a Great Incarnation of the Buddha (daigongen). Anthropomorphic iconography exists of Kompira Daigongen riding the mountain in the form of a white elephant - a creature associated with the Buddha, having served also as the mount of the ancient Hindu god Indra.

In time the Shinto-Buddhist hybrid Kompira Daigongen became identified with the Shinto kami of Mount Kompira, O-kuni-nushi-no-mikoto, one of the founding gods of Japan who was vaguely associated with crocodiles in the White Hare of Inaba myth in the Kojiki. A component from Chinese culture was later assimilated with the identification of the Buddhist and Shinto divinities atop Mount Kompira, with Daikokuten in the guise of one of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune. In iconography he carries a bag like the kami O-kuni-nushi, with "Daikoku" a double pun on the Chinese characters for "O-kuni."

Two more triads can be documented. The second on Mount Kompira is an Eastern Pure Land Triad of the Medicine Buddha Yakushi Nyorai as ruler, Kompira Daigongen as delegate, and Fugen Bosatsu as attendant. Here Fugen (Sanskrit: Samantabhadra Bodhisattva) rides a white elephant in iconography and has been closely associated with the Shingon Buddhist temple on Mount Kompira.

Near the opposite and lower end of the Zozuzan mountain range is a little-known temple with the prefix Mount Lion. Monju (Manjusri Boddhisattva) has been viewed as riding Mount Lion, whereas Fugen rides Mount Elephant, just as they are portrayed in Buddhist iconography. Finally, between these two mountains are the Five Peaks, associated with those noted in pre-Han dynasty Daoism [Taoism in China]. They are also seen as the Five Wisdom Buddhas central to esoteric Buddhist mandalas and especially carved inside the [five-story] Great Pagoda of Zentsuji [see companion article on Shikoku]. Among the temples on Mount Five Peaks, two stand out: Mandaraji, where Kukai dedicated the dual mandalas that he brought back from China, and Shusshakaji, literally the "temple where the Buddha appeared" to Kukai. Thus, in a process of what can be called iconographic association, the whole Elephant's Head Mountain Range might have been perceived esoterically as a Buddha Triad (Shaka sanzon) arranged in the customary fashion with lion-riding Manjusri to the left and elephant-riding Samantabhadra to the right. Practitioners could enter such a complex as though it were a gigantic mandala. Few sites anywhere embody such an overlay of religious traditions.